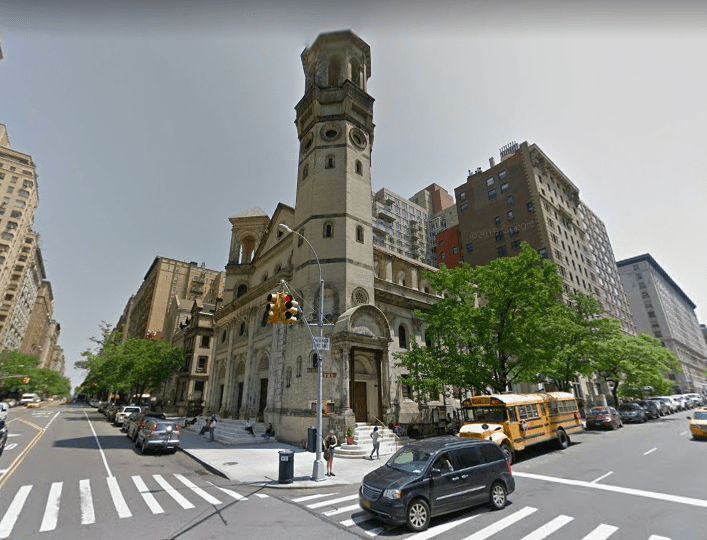

The Church of Saint Paul and Saint Andrew at 263 West 86th Street (Google Maps)

The Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew may need some divine intervention to maintain its 125-year-old building if it cannot find other avenues, so the church is brainstorming some creative ideas, including the sale of air rights to developers.

Advertisement

St. Paul and St. Andrew, at 86th Street and West End Avenue, is in need of some $25 million to repair its roof and fix up its facade to comply with Landmarks Preservations Commission guidelines. Senior pastor K Karpen says the church is desperate for funds: “This building was not built for the ages.”

Selling air rights to developers is under consideration, as reported by Crain’s New York Business. That means developers can purchase the empty buildable space associated with a property—typically on top of or adjacent to a building—to increase the size of their projects and erect buildings as tall as they can. Under current zoning, though, it would be impossible to do that, as St. Paul and St. Andrew is in a historic district. But the pastor is hoping zoning laws can be changed, as was done in Midtown East in 2017. The changes “broaden[ed] the range of area that [religious] institutions could sell air rights to,” says Rev. Karpen. The rezoning allowed landmarked buildings to sell air rights anywhere within a 78-block area. St. Bart’s ended up selling air rights that were a few blocks away. “We’re open to anything that would help us get the building to a place where it can continue living into the future,” says the reverend.

READ MORE: “Distressed” UWS Buildings Placed on HPD List; Must Address Violations Swiftly

Another idea is for the city to pitch in, says Karpen. Because the city has such strict laws governing separation of church and state, that seems a stretch. However, a strong argument for city help could be made, says the reverend, because the church is a landmarked building—landmarked for its beauty, not for the religious activity that transpires inside—and that it is a “public good.”

The church has also looked into the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s provision for “hardship proceedings”—but that seems to be only “theoretical,” says Karpen.

The site was purchased in May 1894, and the church, dedicated in 1897, was built in a style called “scientific eclecticism—which refers to a design that incorporates styles from other architectural periods. It was designed by architect Robert H. Robertson and built at a cost of $343,673.52, including land.

Advertisement

The building was landmarked in 1981, over the objections of parishioners, who had wanted it torn down because it had fallen into such a state of disrepair. They planned to “put up something in cooperation with some housing or something that would help pay for the building” and challenged the landmarking, saying it violated constitutional religious expression rights, says the pastor. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear it.

The church joined forces with B’nai Jeshurun (at 257 West 88th Street) in 1990; they joined their programming and worked on repairs together, getting some (but not enough) done. A landmarked status makes repairs on buildings costlier than they’d otherwise be, since they have to be done according to the highest standards. At this point, in addition to fixing the roof, necessary repairs include reproducing the terra cotta ornamentation on the facade. Because the ornamentation is terra cotta—basically pottery—water gets in its cracks. And it is held in place with metal anchors; over time, they deteriorate as water seeps into the building. “We’ve gone over the exterior of the building multiple times to make sure everything is safe. That is first and foremost. But to actually restore the ornamentation, we’d need to make molds and recast the terra cotta. The LPC says it has to be ‘reproduced in kind,’ as terra cotta.” The repairs that are needed now would all be “exceedingly costly.”

For news across the park visit EastSideFeed.com

To help it survive, the church has joined forces with institutions other than B’nai Jeshurun. Before the pandemic, five congregations were holding services there (but now only three congregations are doing so). The building also lets other entities lease space as well. It is currently home, for instance, to the New Plaza cinema.

Advertisement

The church also houses the West Side Campaign Against Hunger food pantry; it was spun off as a separate entity, but they still partner on feeding thousands of needy families every year. It is working on bringing back its homeless shelter, which was paused during the pandemic.

The church has raised money from its parishioners before, who, the Rev. says, are as generous as they can afford to be. A year and a half ago, it raised “$300,000 to do a small portion of the roof,” but $25 million is a different story.

Karpen says religious institutions all over the city are facing similar challenges, trying to keep up aging edifices. Many are landmarked, as they were “built to be beautiful.”

Is the church’s survival really worth wrecking the West End Avenue skyline and setting a precedent for more such “development?

If the church sold the building, the building wouldn’t come down, and any developer of the space (I assume the interior is not landmarked, so it could become apartments) would treat the air rights as an asset to be sold.

Landmark rules need to be updated and get with the times. There is no reason to use identical historical materials (terra cotta, wood, etc) when longer lasting materials can be used to the same aesthetic effect. It makes no sense to require terra cotta exterior tiles that are expensive and water permeable, when identical looking tiles can be made from other materials. Similarly many buildings cannot afford to replace leaky and energy inefficient facade windows because LPC requires identical wood, which costs 3x-10x more to install, is more expensive to maintain, and does not last as long as metal which can be made to look like the wood it would replace. Landmarks should be happy to preserve the look, not the actual materials, which are no longer used for good reason.

The LPC requirements are cost prohibitive, causing the very buildings LPC wants to preserve to fall into further decay.

The LPC doesn’t require identical historical materials in all cases, look at those ugly (LPC approved) fiber glass stair rails on so many “restored” brownstones in landmarked districts and in specifically landmarked buildings.

It is extraordinarily more expensive to shape metal to match old wooden window and door frames, but if that matching isn’t done the “restorations” look horrid. There are materials to consider, but they are not metal, and their use would require that shops and small factories be set up to match the old wooden frames being replaced with modern materials, but that’s not inexpensive.

NO. They already pay $0 in taxes. If their flock can’t cough for the love of god, sell the joint.

Sound good to me. The first amendment calls for freedom of religion, not a free ride.

Thanks god for the churches— without them we would just have more boxes or sky high pencils of housing for the rich & investors…

I know that’s only a summary.

We saved the church at 86th and Amsterdam next to Barney Greengrass so do this one too Gale Brewer!!!

TY, Neal

Neal,

It’s not a question of the tearing down the church, But the church may sell the air rights, and that means another one of “those towers”.

Is the church on Amsterdam landmarked?

Gail Brewer: outside of extraordinary cases, it is incredibly difficult for the government to provide direct aide to a church in the USA — this is as it should be.

I am all for preserving the building—but the church should spread their ideas more widely. The building serves as much as a church to multiple congregations who hold services there, in many languages and religions but it also hosts many other events. It is a community center that holds films, performances, and talks (all impacted by the pandemic, of course); is the local food bank; and is our local polling place. During heavy-turnout elections, the sanctuary is used as a staging area so those waiting to vote do not have to wait outside and the parishioners set-up hospitality with cookies and music. It is always very welcoming and makes voting a joy.

If the church could more formally divide the space they have and host more rentals for events (commercial as well as non-profit), it would help. Defining some spaces for secular, but non-profit, use could also help them get City funding and other grants to shore up the obvious material needs. (The steel framework holding up the one portico is frightening.) This church is more than that, it is a community gathering place—which would be lost by privatizing it.

So chop it up inside like an old movie theatre.

I went to a ticketed event there, about 12 years ago, and all the seats (balcony included) were taken/sold.

Clearly that was popular speaker, but what you’re describing is chopping up a light filled space, so in that particular it’s not like making a multiplex out of an old theatre.