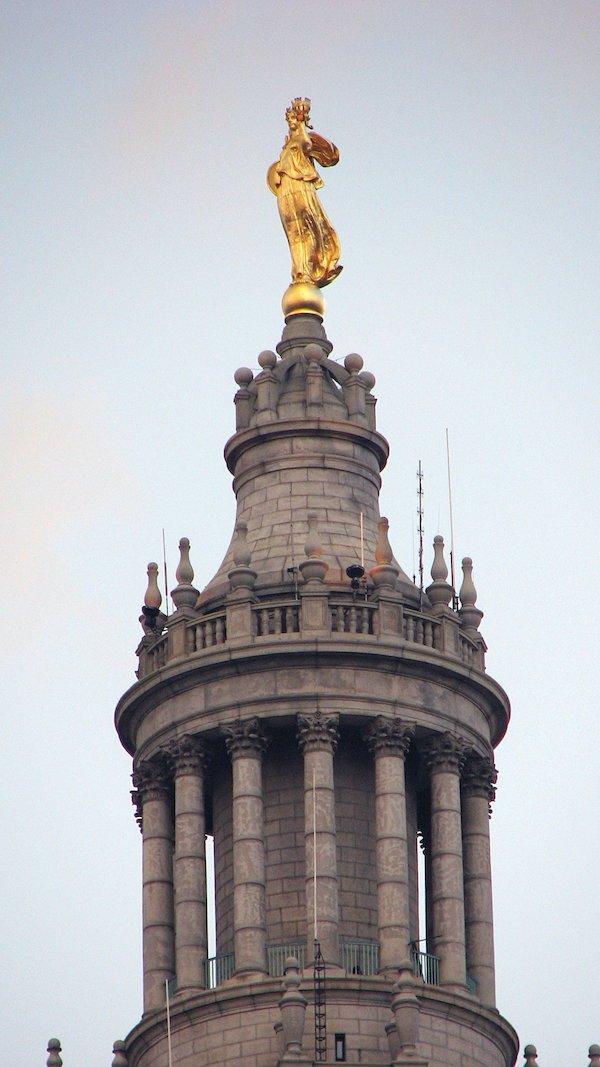

In 1974, Bill and Willow Hagans traveled from Detroit to New York City to be married at City Hall. Watching over their ceremony from high atop the Manhattan Municipal Building stood Civic Fame, a thirty-foot gilded statue by Adolph Alexander Weinman. Hettie Anderson was the model, but as Bill and Willow spoke their vows, that name meant nothing to them.

Photo: Valeriy Ovechkin Mod2106 via Wikimedia Commons

“Well, we didn’t talk too much about her because she was taking her clothes off at a time that was inappropriate,” Mamma Jeanne replied.

“What was she taking her clothes off for?”

“She was an artist model.”

[/perfectpullquote]

As Mamma Jeanne began to reveal their family history, Willow called out to the next room, “Bill are you listening to this? Take notes. Start writing.”

Advertisement

That chance conversation turned into a life-long adventure for Bill and Willow. Together, they would spend the next 40 years working tirelessly to uncover the fragmented history of their cousin, Hettie Anderson.

In the mid-1890s, Hettie Dickerson, a light-skinned African American “girl with the figure of a goddess” moved from Columbia, South Carolina to the Upper West Side of Manhattan with her mother, Caroline. They came from an educated family of brass musicians, seamstresses, physicians, pharmacists, academics and politicians, escaping the brutal conditions of a post-Civil War south. Hettie, then in her early 20s, enrolled and modeled at The Art Students League and for an unknown reason changed her name to Hettie Anderson. After only a brief period in NYC, she became a central figure in America’s art world and a favorite model of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Anders Zorn, John La Farge, Adolph Weinman and others.

READ MORE: Maya Angelou’s Upper West Side Life

An intimate 1897 Anders Zorn etching reveals a nude Hettie, lounging behind a weathered Augustus Saint-Gaudens. It was once believed to be Saint-Gaudens and his mistress, Davida Clark. However, in 1982 a picture of Davida Clark was published and bore little physical resemblance to Zorn’s etching.

Anderson depicted behind Saint-Gaudens in an etching by Anders Zorn, 1897. Anders Zorn, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Advertisement

Circulation of the coin only lasted a few years and in June 2021, a coin from 1933 sold at Sotheby’s for nearly $19 million, breaking auction records. In 1907, Augustus Saint-Gaudens died, ending an era of intense collaboration fueled by mutual respect and admiration.

Unknown author, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In 1913, Civic Fame by Adolph Weinman was unveiled on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building without crediting a model and leading to speculation. Although different models have been credited to this monumental 30-foot sculpture, an issue of Architectural Record from June 1913 provides clarity. In the issue, Charles H. Dorr states, “…there has been considerable speculation as to her identity. It might be interesting to note, however, that she is a New York girl, and posed for the figure of Victory…by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.”

Artist’s model Hettie Anderson, bust by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, photographed by De Witt Ward. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hettie would live with her mother in the same home on the Upper West Side for the rest of her life. Eventually she worked at The Metropolitan Museum of Art where she was well respected and financially supported, but she struggled with mental illness throughout the final 20 years of her life. In a 1920 letter to Henry Watson Kent, The Met’s secretary of board of trustees, Hettie is described as having “ideas of being stared at when she is on the street and of being influenced by some strange power which she cannot understand.”

READ MORE: A Day in The Life of Bobby: Discovering Virgil Fox

Her mother, listed in the New York censuses as white but “colored” in South Carolina records, died in 1928 at the age of 88. Hettie continued living in the same apartment, at 698 Amsterdam Avenue (between 93rd and 94th streets). The 1930 census states that Hettie was unemployed and white. On January 10, 1938, Hettie died of heart failure, alone in her Upper West Side home. Her estate, worth tens of thousands of dollars, was given to her nieces and nephews and her legacy was largely forgotten for 40 years. Until a couple in Michigan decided to share a cup of tea with their grandmother.