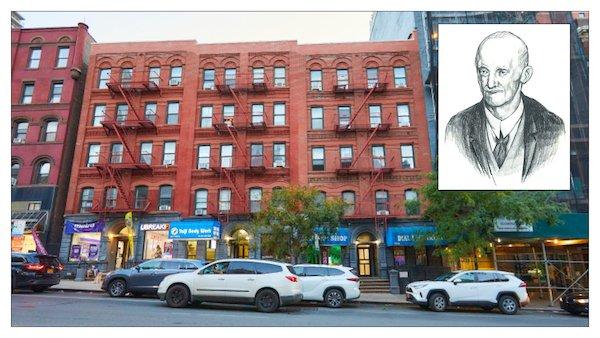

Emerich Juettner’s apartment building at 204 West 96th Street, by Lee Uehara. Inset: Sketch of Emerich Juettner, courtesy of the U.S. Secret Service.

It was pure chance – and a fire – that a junkman in his 70s residing on the Upper West Side with his dog got nabbed by the U.S. Secret Service for a decade-long counterfeiting scheme passing $1 bills in and around the neighborhood.

Advertisement

Emerich Juettner, a widowed father and retired building super who lived with his nameless mutt, passed the fake bills starting in 1938 to make ends meet at his $25-a-month apartment at 204 West 96th Street. That is, until the winter of 1947, when some neighborhood boys stumbled upon Juettner’s hand-crank printing press, engraving plates and some of the counterfeit bills after they were left in the snow.

Firemen at the time had surveyed the damage in Juettner’s 5th floor walk-up, two-room tenement apartment and thrown out random junk including the printing equipment outside a window behind the building to clear out some of the debris. A snowfall hit shortly after, and it was during the thaw that the lads saw some of the $1 bills peeking out of the junk pile. The boys, between the ages of 10 to 15, then began trading toys and items amongst themselves for Juettner’s printing equipment and fake money – at which point parents reported the findings to the U.S. Secret Service. This is the agency which oversees counterfeiting and the president’s security detail.

At the time and unbeknownst to him, Juettner was the most-wanted counterfeiter in U.S. Secret Service history; he kept agents pinning thumbtacks on a New York City map at locations where the fake money was spent for ten years. However, during that time, the U.S. Secret Service successfully convicted more than 1,000 other counterfeiters and seized more than $3 million.

Advertisement

Yet, this case was unusual because of Juettner’s age; his using only $1 bills; never shopping at the same store twice; and keeping track of where he passed the fake money to avoid repeat visits, a U.S. Secret Service spokesperson told ILTUWS.

“What makes it unique isn’t the threshold – but the denomination of one dollar. If you’re going to go to the lengths of a dollar, why not go for a larger denomination, why not go for a bigger bang for your buck?” the U.S. Secret Service spokesperson said. “It was not as if he was passing hundreds of thousands of dollars of currency.”

It appeared that Juettner’s goal was survival, not greed. Juettner’s fake money traveled as far as Seattle, Atlanta, Baltimore and Denver. His aliases also included the names Edward Mueller, Edward Miuller and Edward Muller.

The incredulous part of this counterfeiting scheme is that Juettner’s ability to replicate a dollar bill was terrifically awful by any counterfeiter’s standards: George Washington’s name was misspelled, “Wahsington”; regular stationery paper was used; and on the engraving plate, Washington’s left eye was a mere spot and his shirt looked soiled, among other gaffes, according to a Secret Service report in an article by The New Yorker, Old Eight Eighty, by St. Clair McKelway.

McKelway’s three-part series was so popular it was turned into a 1950s highly romanticized movie, Mister 880, starring Burt Lancaster and Edmund Gwenn in the lead role. Gwenn also portrayed Santa Claus in the classic, Miracle on 34th Street. The rights to Juettner’s story made him more than the $5,000-plus he printed over the years, and later when asked if he would go back to counterfeiting, he reportedly said no because “there wasn’t enough money in it.”

Advertisement

Another turn in this story is that the U.S. Secret Service called for leniency in sentencing. Through many interviews with neighbors and store owners, agents found that people only had nice things to say about Juettner, who was described as a helpful and likeable bald fellow at five-foot-three-inches tall, with bright blue eyes. Other factors involved with the lighter jail time included the senior readily admitting to his wrongdoing and in great detail, his age and his lack of avarice.

Juettner, who reportedly learned how to engrave as a youth in Austria, told authorities that he only printed and passed enough fake money to feed himself and his dog. He also said he didn’t want to worry his children by telling them of his financial situation. Originally, Juettner’s sentence was nine months, down from a possible 15 to 30 years. However, the judge gave him a sentence of one year and one day so that Juettner would be eligible for parole in four months. And the mandatory but nominal fine: $1.